|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

박영훈: 미적분의 미술적 세계

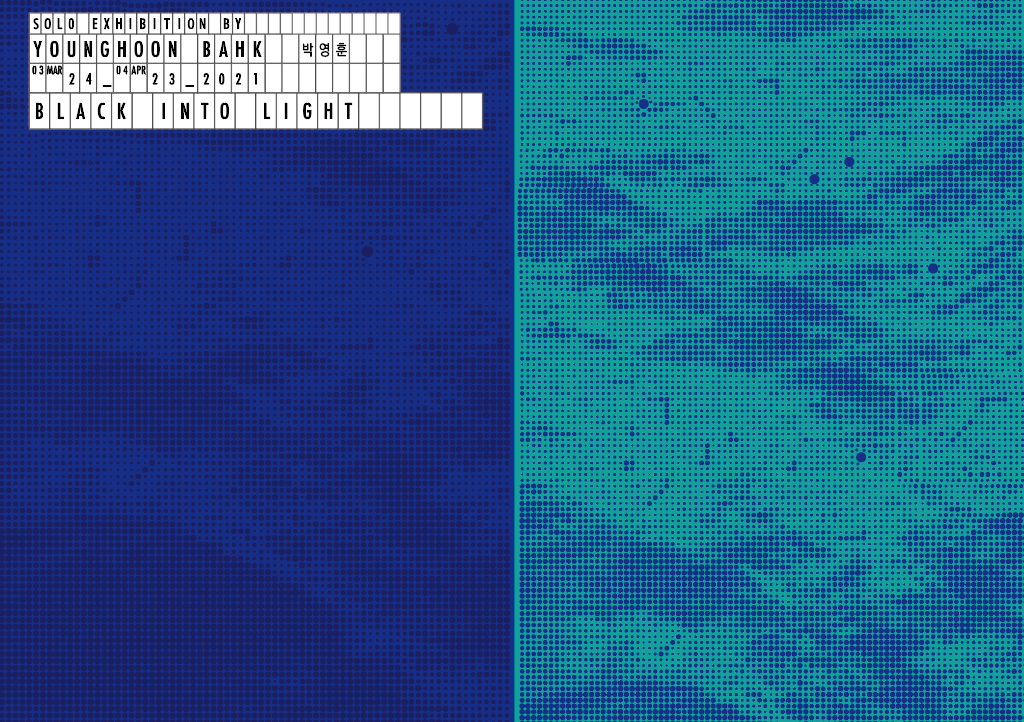

“애초에 법이 없으며, 주체인 내가 한 번 그음으로써 모든 법이 생겨난다.” 명말청초의 천재 화가 스타오는 자신의 화론(石濤畵論)을 이렇게 시작한다. 그래서 일획이 만획이 된다. 마르셀 뒤샹(Marcel Duchamp)이나 존 케이지(John Cage)와 머서 커밍햄(Merce Cunningham)이 주장하는 “개념”, “소음”과 “일상의 몸짓”이 미술이고, 음악이며, 무용이라는 소리도 같은 맥락이다. 절대적 개인으로 아티스트가 자신의 세계를 자기 예술의 최소 단위로 환원하여 그라운드 제로에서 작품으로 재구성하여 출발한다는 것이다. 박영훈의 회화 작업도, 같은 맥락에서, 한 점의 점에서 시작하고 끝난다.

미술사에서 점을 하나의 최소 추상 단위로 환원하여 그 점으로 구성하는 작업은 흔한 일이다. 조르주 쇠라(Georges Seurat)부터 폴 시냑(Paul Signac), 로이 리히텐스타인(Roy Lichtenstein), 데미안 허스트(Damien Hirst) 등에 이르기까지 적지않은 예술가들은 점과 점 사이에서 발생하는 색채의 효과를 노리는 작품을 제작해왔다. 게다가 디지털 매체가 발달하면서 망점이나 픽셀이라는 최소 단위 디지탈 이미지를 사용해서 작업하는 일도 흔해졌다. 박영훈도 그 흐름 속에서 작품을 진행하였다. 박영훈은 점을 최소 단위로 환원된 “영점추상(Abstraction Degree Zero)”가 아니라, 점 자체가 형태를 가진 꽉 찬 작은 덩어리, 물질로 된 입체다. 캔버스 위에서 재현되는 점은 점이면서 면이고, 형태며 색인 모든 것의 재현이 된다. 또한 점은 재현이면서도 픽셀이나 망점처럼 그 자체 외에는 아무 것도 의미하지도 지시하지도 않는다. 캔버스 표면 위에 하나하나 그 점들을 붙이는 행위를 통해서 점들은 마치 전통적 페인팅에서 붓질(brushstroke)같은 효과를 드러낼 뿐만 아니라, 예술을 통한 본인의 수행적 의지와 태도라는 비물질적인 아이디어를 구현하려는 노력의 결실이다. 그 결과 박영훈의 점은 그것을 통해서 우리가 살아가고 있는 세계를 보는 아티스트의 눈과 그 세계를 붙잡으려는 의지처럼 보일 수 밖에다.

박영훈은 얇은 반무광 칼라알루미늄을 6가지 사이즈, 5가지의 형태의 작은 덩어리로 기계를 사용하여 잘라서 의료용 핀셋으로 캔버스 위에 옮겨 붙인다. 그리고 무광 투명 우레탄으로 도장까지 하면서 어마무시하게 시간과 노동을 잡아먹는 한 점의 작품을 완성한다. 얼핏 보면 반도체 회로판이나 배전판처럼 기계로 찍은 듯이 보이는 회화작품이 사실은 10,000개가 넘는 작은 덩어리로 이루어진 미니어처에 가까운 조각설치 작품에 가깝다. 항공에서 내려다 본 도시의 모습이나, 디오라마, 또는 건축 개발 모형도처럼 보이는 것이다.

가까운 거리에서 작품을 보면 그 점들을 입체적으로 조감할 수 있고, 그 점들이 만들어 내는 입체적 질서를 지각할 수 있다. 하지만, 작품에서 멀어지면서 거리가 생길 수록 그 입체적 캔버스가 평면적인 색의 향연처럼 보이다가 급기야는 색이 만들어 내는 빛으로 보이기 시작한다. 거리에 따라서 작은 입자들이 구성되고 배치되는 시각적 자극에서 점차 형태가 사라지며 색으로, 마침내 급기야 빛으로 보여 형태가 사라지는 놀라움을 관객들이 체험할 수 있다. 색으로 빛으로 인지되는 체험 속에서 그 형태 자체가 의미나 개념으로 전환되어 가는 것이다. 관객들은 물질에 포박되어 있는 물질성이라는 고정 관념에서 벗어나는 자유라는 감각을 만끽할 수 있는 여정에 참여할 수 있게 된다. 박영훈 작품이 부리는 마술적 효과 때문에 갤러리라는 건축적 공간은 색 속에서 물질이 사라지는 감각적 공간으로 탈바꿈 한다.

마치 라이프니츠적인 세계에서 완결된 최소 단위인 모나드들이 모여서 조화롭게 구성되는 거대한 세계처럼, 박영훈의 회화는 그 자체가 원인이 되는 완전체다. 하나하나의 점들이 모든 원인의 바깥에 존재하는 아티스트의 손을 통해서 &운명&으로써 작품이 우리에게 제시된다. 자체 완결적인 점들이 그대로 예술가의 지각과 욕구로 수렴되면서, 또 다른 완전한 세계가 하나의 작품으로 창조된다는 것이다. 마치 한 없이 쪼개져 더 이상 쪼개질 수 없는 최소 단위를 만들어서, 그것들을 다시 쌓아가는 이 예술적 작업의 과정은 수학의 세계처럼 엄밀하고 정직하다. 달리 미분이고 적분이겠는가. 스스로 완성되고 완결된 박영훈의 고독하고 고상한 낭만적 내면이, 그 누구에게도 열어보이지 않던 자기만의 세계를 매우 도발적으로 수줍게 드러내고 있다.

(김웅기, 미술비평)

Younghoon Bahk: The Aesthetic World of the Infinitesimal Calculus

“No law exists before the one stroke that generates it all,” writes Shitao, a genius painter from the Ming-Qing transition period, at the beginning of his aesthetic theory. A connection can be made with Marcel Duchamp’s “concept” that becomes art, John Cage’s “noise” that becomes music, and Merce Cunningham’s “daily gestures” that becomes dance. The artist, who is at the vertex of individualism, creates a work of art at ground zero with the particularity of their world as its smallest building blocks. Younghoon Bahk’s painting, similarly, begins and ends with a single dot.

In the history of art, there are numerous examples where a dot is applied as the smallest abstract unit in constructing an image. From Georges Seurat, Paul Signac, Roy Lichtenstein to Damien Hirst, many artists have created works using the effects of color that occur between these dots. With the development of digital media, even pixels and halfpoint dots have been employed as the smallest unit to create art. Younghoon Bahk’s work can be placed within this spectrum. However, Bahk’s dot is not simply the smallest unit like the “Abstraction Degree Zero.” Rather, it is a small three-dimensional “thing” that has a solid mass with its own shape. A dot is materialized on canvas simultaneously representing a point, surface, shape, and color; it is the re-presentation of all things. Even though a dot is a representation, it does not signify or indicate anything other than itself, just like a pixel or a halftone dot. The artist’s gesture of attaching each dot on the surface of the canvas not only evokes the effect of a brushstroke in traditional paintings, but also proves the artist’s cumulative effort in realizing the impalpable metaphysics of his meditative volition and approach towards art. As a result, Younghoon Bahk's dot is inevitably the artist's perspective of the world we live in and his determination to hold on to it.

Younghoon Bahk takes a thin semi-matte colored aluminum and cuts it with a machine into small pieces of 6 different sizes and 5 distinctive shapes. He then attaches each piece onto a canvas using a medical tweezer. Finally, he paints over the entire canvas with matte and transparent urethane. Such a process is undoubtedly time consuming and labor intensive. Though at first glance, his painting may look like a semiconductor circuit board or a distribution board that is produced in a factory, it is in fact closer to a miniature art installation made up of over 10,000 small individual pieces. It echoes the aesthetic of an aerial view of a city, a diorama, or a model of architectural development.

At close distance, numerous three dimensional dots are conspicuously composed in an orderly fashion and its visual experience is stereoscopic. However, as one moves away from the work, the three dimensionality of the canvas transforms into a feast of flat colors, and eventually one is left with light exuded by colors. Subjected to the viewer’s position, the visual stimulus caused by the composition and arrangement of the work’s smallest units loses its shape and gradually metamorphoses first into colors then to a beam of light. Within the experience of color and light, form itself becomes meaning or a concept. As the viewer is liberated from the general understanding of a “thing” in its materiality, they can participate in the journey of freedom as a form of sensation. By virtue of the magical effects of Bahk's work, the physical space of a gallery is transformed into a sensuous space where matter fades into color.

Like Leibniz’s monumental world harmoniously composed with monads, categorically the smallest unit of existence, Younghoon Bahk’s painting is in itself a totality that is caused by its own volition. Each dot is placed by the artist’s hand that is external to all causes, serendipitously presenting the work to the viewer. As every dot with its own sovereignty enters the artist's consciousness and desire, the final creation is yet another ideal world. The process of creation demands an inexhaustible amount of severing to the point of the smallest unit only to rebuild from it again, like the rigorous and virtuous world of mathematics. It is no coincidence that calculus has two major branches, the differential and the integral. The solitary, virtuous, and romanticized inner workings of Younghoon Bahk that have been cultivated and perfected by the artist alone, finally reveals its world that has never been seen by anyone. It is by all means provocative and tentative.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|